Current Nature: Capturing A Place In Time - The Importance Of Herbaria

Nathan Ernst - Conservation Research And Stewardship Fellow at the Linda Loring Nature Foundation •

Now more than ever we live in a world abound with change. Changing temperatures, sea levels, species compositions, and precipitation amounts are only a few of the many environmental changes that our natural world is witnessing as we see the effects of our own anthropogenic influence. Here’s the thing: we can’t make sense of the change upon our environments without first understanding their past. One way to capture this change is through herbaria: collections of pressed plants, typically with notes describing the time and place they were collected - acting as a library for plants. On one hand, herbaria are a useful tool in learning how to identify various flora, hence why many universities and education organizations maintain a local herbarium - nothing’s better for learning than the real thing! In fact, prior to modern photography, herbaria were the only way to officially record a species at a place and time. Even today, if you look closer, the specimens within an herbarium act as representations of the place and time from which they came. In essence, these specimens, along with the notes that accompany them, capture a moment in time of a place’s natural history.

To truly grasp why these often underappreciated collections are so crucial, it’s important to understand the process a herbarium specimen must go through before being put in the hands of avid naturalists.

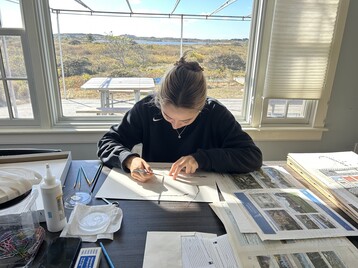

Firstly, “the collector” goes into the field to collect any specimen of their choice. Be it leaf, lichen, fern, or flower, herbarium mounts can be made from a variety of flora. Reproductive structures are often included in order to most accurately identify the specimen, but the part of the plant collected depends on the goals of the collector. Depending on the herbarium, collectors take notes on characteristics such as the species, habitat type, surrounding vegetation, and anything else that may be of note to the collector. After collection, the specimen is placed in a plant press where it’s sandwiched between blotting paper, newspaper, and cardboard until it’s dry and ready to be mounted. Plants are pressed and dried to preserve them by removing moisture, which prevents decay. Once pressing is complete, the curator uses a combination of non-corrosive glue and/or tape (depending on the preference of the preparer) to adhere the specimen to a piece of mounting paper. It’s important to display the plant in as close to a natural position as possible while ensuring that its distinguishable characteristics are discernible for viewers. While generally prepared for scientific purposes, this is where a bit of artistry comes into play. Finally, after all that work is complete, the specimen is ready to be put in the hands of countless curious plant enthusiasts!

Environmental change here on Nantucket is evident year by year, with more frequent and intense droughts and rising sea levels becoming the new normal. Given this, understanding our local natural history through herbaria allows us to peer into what our flora may have looked like in the past, thus allowing us to compare it to the flora of the present. In fact, when looking at LLNF’s herbarium collection of goldenrods, Dr. Sarah Bois, LLNF’s Director of Research & Conservation, noted that the golden-yellow flowers of the preserved specimens were notably more vibrant than the drought-stricken individuals currently in bloom on the property - and that’s just a single example from an individual year.

With some specimens dating well over a century old, a multitude of changes can be deciphered from herbarium collections, such as changes in distribution, phenology, size, color, commonality, and a whole lot more. Depending on the notes taken upon collection, herbaria are often used for in-depth, long-term research as well. For example, when cross-referenced with climate records, one can get an insight into how observed changes in a species’ natural history align with environmental change. By looking at a combination of specimens, you can even look beyond the species level and look at the change in composition of a local plant community over time. On another hand, researchers can dig even deeper by using herbarium specimens as a source of genetic sampling to gain insights into environmental or even evolutionary changes!

Frankly, herbaria and the notes they provide allow us to not just look at the plants themselves, but the changes in the ecosystems that they’re a part of. Moreover, herbaria don’t just let us peek into the past, but they also allow us to monitor the present. In doing so, we can take note of any environmental changes we are seeing, thus allowing us to become more informed stewards of the land we manage.

The best part is that you don’t have to be a researcher or go to the Smithsonian to access a herbarium. In fact, here on Nantucket we have multiple herbaria documenting Nantucket’s natural history, with collections at the Linda Loring Nature Foundation, the Nantucket Conservation Foundation, and the oldest repository on the island at the Maria Mitchell Association. These herbaria are crucial learning tools for both the public and researchers alike. Be it past or present, these documentations of natural history are for everyone, allowing anyone to see the natural world from a moment in time.